Fighting female genital mutilation, one Kurdish village at a time

By Patrick Markey

TUTAKAL, Iraq (Reuters) - Amena practiced female genital mutilation in her remote village in Iraqi Kurdistan for so many years that she struggles to recall how many girls passed through her hands.

"I couldn't count them," said the midwife, sitting in a garden in Tutakal, her hair in a black headscarf and her chin marked by a faded traditional blue tattoo.

"Ten children, a hundred children, a thousand children, I just can't count how many."

More than a year after lawmakers in Iraq's self-governed Kurdistan region passed a law banning FGM - also known as female circumcision - activists say the practice still goes on.

Autonomous from Baghdad since 1991, Kurdistan has its own government and enjoys an oil boom that has helped make it one of Iraq's safest areas, enjoying modern services, glitzy hotels and shopping malls unavailable in the rest of the country.

In remote rural areas, however, ancient traditions often rule. Honor killings, where women are murdered to protect the family's honor, still occur, and FGM is widespread, in part because it is supported by some clerics who say it is part of sharia or traditional Islamic law.

This could be changing, however.

In Tutakal, the donation of basic school services and a small classroom by a German-funded non-governmental organization called WADI has helped convince residents to stop the practice.

It is a promising model, activists involved in the campaign to stop FGM say, one they hope will spread to other Kurdish villages. The activists work to convince villagers the practice has no basis in Islam and spread the word that it is now against the law.

"More people understand this is a crime, and they can't practice it anymore, but we still need to implement the law," said Suaad Sharif, a field worker with WADI. "They say their grandmothers did it, their mothers did it, it was a habit that they had to carry on."

ACROSS AFRICA, MIDDLE EAST

According to the World Health Organization, female genital mutilation -- the partial or total removal of external female genitalia -- is practiced in countries across Africa and in Asia and the Middle East for cultural, religious and social reasons.

Some practitioners believe FGM will prevent sex before marriage and promiscuity afterward; others say it is part of preparing a girl for womanhood and is hygienic.

It can cause bleeding, shock, cysts and infertility, but also severe psychological effects which campaigners say is similar to those suffered by rape victims.

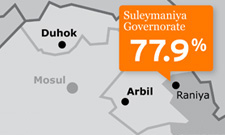

As many as 40 percent of women and girls in Kurdistan have been subjected to the procedure, according to New York-based Human Rights Watch, citing government reports and activists. A survey by WADI found up to 70 percent of women had suffered from FGM in some Kurdish areas.

The roots of the practice in Kurdistan are unclear. Beyond the ethnically mixed city of Kirkuk, the practice is less common in other parts of Iraq and in Kurdish areas in neighboring Turkey.

But where illiteracy and poverty are high in Kurdistan, so too is the number of woman who are circumcised, and the prevalence of conservative Islam in these areas also appears to play a role.

"They related this to sharia practice, and this is how they educated these communities about this," Suzan Aref, head of WEO, a woman's empowerment group in Kurdistan.

Kurdistan's parliament won praise from rights organizations when the law criminalizing the practice went into effect in August last year. But in a statement earlier this year, Human Rights Watch criticized the government for not doing enough to enforce the ban, including by making sure police and government officials were educated and on board.

Pakhshan Zangana, secretary general for the Kurdistan's High Council on Women's Affairs, said the law had succeeded in reducing the numbers of female circumcisions but acknowledged that some of the practice was going underground.

"They do it secretly because it is against the law," she said.

A WELCOME CHANGE FOR SOME

In Tutakal, three hours from the Kurdish capital Arbil reached only by dusty tracks weaving through the mountains, FGM has been practiced for generations.

All but two of the women and girls from about 17 families in the farming hamlet have been circumcised, most at as young as four years old.

For many of the families, it was simply a tradition passed down from grandmother to mother to daughter in the belief that girls who failed to go through the ritual were "unclean".

For women like Golchen Aubed, 50, social pressure also played its part. Like many of the mothers in Tutakal, she felt the practice was wrong but allowed her daughters to be circumcised by the community midwife just as she had been herself.

"In our culture when you don't do this, everyone else asks why," she said sitting on a carpet in her home with her youngest daughter, Sharaban. "Why should I stand out? I knew it was bad, I knew it hurt the child, but even so I went ahead."

Her son refused to allow his own daughter to suffer the same way -- she is one of the two small girls in the village to escape FGM. No girls have been circumcised since Tutakal's elders signed the agreement with WADI in September last year.

"He says now that if he finds out about anyone doing this he will go and report them to the police," Aubed said.

The decision to stop the practice was a pragmatic one for village elders in Tutakal after the campaigners volunteered the school services and new classrooms.

Prefabricated facilities have replaced the ramshackle mud-brick and wood room that used to serve as a school. Older children are provided with transport to a nearby town where they can attend middle school.

Amena now lives without the work that brought her meager income from her village, from nearby towns and even Kurdish communities in neighboring Iran.

"They should find me some alternative," she said. "Everyone knows I am alone that I don't have a husband, a father or a brother or son to look after me."

But the elders have no regrets about their decision.

"When they do this, they cut a piece of flesh from a woman," said headman Sarhad Ajeb, sitting on the floor of Tutakal's simple mosque. "There is no mention of this practice in the holy Koran."

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation