Tackling Female Genital Mutilation in the Kurdistan Region

By Sofia Barbarani

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) is defined by the Word Health Organization (WHO) as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons”. It is a practice rooted in flimsy accounts of religious traditions, mythical beliefs, and purely aesthetic reasons and is recognised internationally as a form of violence against women. FGM often leads to long-term physical and psychological problems, as well as death.

Whilst new reports released by the UN point to fewer girls being subjected to FGM, the numbers are still alarmingly high. WHO estimates that between 100 and 140 million girls and women worldwide have been subjected to FGM.

In a symbolic move, the practice was banned on 20 December 2012, following a unanimous resolution at the UN General Assembly, whilst the 6 of February marked the International Day for Zero Tolerance of FGM.

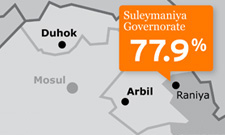

Often considered a uniquely African problem, so much so that stats and figures of FGM in other areas of the world are not easily found, it is also practiced in the West, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. In the Middle East, the rates of FGM are highest in Northern Saudi Arabia, Southern Jordan and Iraq, including the Kurdish region.

A Human Rights Watch (HRW) report concluded that as many as 40 percent of women and girls in Kurdistan have been subjected to female genital mutilation.

Despite the implementation of the Family Violence Law in August 2011, which includes several steps towards the eradication of FGM, HRW has found that the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is yet to take defining steps in implementing this law. Whilst domestic violence is being tackled head-on through awareness campaigns and the training of judges and police, the same steps appear not to have been taken to implement the FGM ban, reports HRW.

Last year, Joe Stork (the deputy Middle East director at HRW) acknowledged the progress made by the KRG in passing the Family Violence Law, yet stressed the need to start an immediate implementation of it. Whilst on the International Day for Zero Tolerance, the UN called on the government of Iraq and the KRG to take additional steps to eradicate this brutal practice.

The difficulties have lain in raising the subject matter and giving a voice to the victims. In a traditional society like the Kurdish one, speaking of a girl or woman’s genitalia (often associated with sexual function and sexual pleasure) is not an easy task.

A more heartening result comes in the guise of German-Iraqi NGO WADI, an organisation which has been combating violence against women in Iraqi Kurdistan since 1993. In a recent study carried out by them, there appears to be evidence for a trend of general decline of FGM. According to their research, less than 50 percent of young girls are being mutilated today.

Following the organisation’s FGM-Free Communities programme, seven villages in the Kurdish region began their battles against the practice. According to WADI, not a single case of FGM has happened in these villages since. Villages who join the network and publicly commit themselves to stopping FGM receive small community projects, which they are free to choose.

WADI stresses the importance behind educating and alerting the villagers to the health and psychological risks of FGM. Midwifes also play an important role as practitioners, and they also must be convinced of the harm they are doing to the village’s girls if they are to stop. To further support women who have undergone the procedure, WADI launched an FGM Hotline project, through which FGM victims are provided with social, psychological, medical and sexual advice.

Today the Kurdistan Region is leading the fight against FGM in Iraq. This is due primarily to a handful of local women and organisations, such as WADI, which have taken the time to educate men and women on the risks of FGM.

As Kurdistan struggles under the weight of an unwavering tribal system, women’s rights are often disregarded due to pressure from tribal leaders and clerics. Regardless, if the KRG is to take its rightful place as a democracy amidst authoritarian regimes, it must regard issues such as FGM of utmost importance.

Sofia Barbarani is a London-based freelance writer, with an MA in Middle East and Mediterranean Studies, King’s College London. Her main focus is Jewish-Israeli identity and the Kurdistan Region.

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation