Iraqi Kurdistan could end FGM in a generation - expert

by Emma Batha

LONDON (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Female genital mutilation could be eradicated in Iraqi Kurdistan within a generation, a U.N. expert said this week as a survey revealed high support for ending what she called an "abominable crime".

The study, released by U.N. children's agency UNICEF, indicated that fewer families than before were having their daughters cut, but also revealed widespread ignorance of the dangers of FGM, which can be fatal and can cause life-long health problems.

Up to 140 million girls and women worldwide are thought to have been subjected to the ancient ritual, which is practised across a swathe of Africa and pockets of the Middle East and Asia.

FGM involves the partial or total removal of the external genitalia and has been internationally condemned as a gross human rights abuse.

"I have been inspired by women in Sudan, Ethiopia, Yemen and Kurdistan who are bravely fighting to protect their daughters from this abominable crime," said Frances Guy, U.N. Women's Representative in Iraq. "In Kurdistan we have a chance to end this practice within a generation. Let's do it."

Nearly 60 percent of women who responded to the survey said they had been cut. But less than 30 percent of women with daughters said they had had their daughters cut. Mutilation rates among those polled fell in younger age groups, suggesting FGM was declining, UNICEF said.

The data indicated girls were usually cut around the age of five. Most people believed FGM was practised for traditional, religious or social reasons. But the overwhelming majority, including religious leaders, said they did not personally support FGM, and only 13 percent of respondents actively wanted to keep the tradition.

UNICEF said the study of FGM practices and attitudes - the first of its kind in the region - would help it break down barriers to eliminating the brutal ritual.

CHILDBIRTH COMPLICATIONS

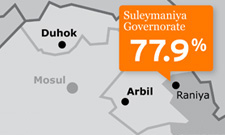

The survey was carried out among 827 households in the northern Erbil and Sulaimaniyah regions, where FGM is most prevalent despite being illegal. It is almost non-existent in most other parts of Iraq.

"FGM is a violation against the humanity of a woman," said Pakhshan Zangana, who heads the regional government's High Council of Women's Affairs, which collaborated on the survey along with other partners.

"The practice robs women of their will, objectifies and dehumanises them and must be completely eradicated from Kurdistan."

Although most people knew the mutilation reduced sexual desire, more than a third of men did not know if the practice harmed women and more than half of all respondents did not know that it could cause life-threatening childbirth complications. Barely a quarter knew it caused menstrual problems and cysts.

Many of the women surveyed reported relationship difficulties with their husbands linked to FGM and more than a quarter suffered psychological problems.

A previous study in Iraq found girls who had undergone FGM were more prone to post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and other psychological disturbances than girls who had not.

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation