Iraqi Kurdistan fights female circumcision

Female circumcision is slowly declining in Iraqi Kurdistan. Years of campaigning and a law against the practise have borne fruit. Some villages went from 100 percent of all young girls being circumcised to none.

"Circumcision brought us problems. It is much better for husband and wife when it is not happening." The mokhtar of Twtakal, a small village in Iraqi Kurdistan is very clear about it. The practice of FGM, or female genital mutilation, should be eradicated.

The village chief is proud that his village has stopped circumcising its women, where only two years ago still every mother had it done to her daughters. It was a bad habit, Kak Sarhad told DW. "For men, who have all these layers, it is cleaner. But women don't have that and don't need it."

The elder women of the village do not agree. "It has been done for generations. Our mothers and grandmothers did it. We had no problems with our husbands, no divorces," say some village women, gathered on the floor in the mokhtar's house.

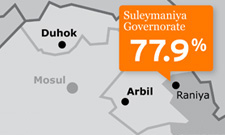

Twtakal is one of the six villages that became "FGM Free," in a project launched by the German-Iraqi organisation WADI. The isolated village which houses 13 families is one of the success stories, and illustrates a slow trend toward a decline in the practice in Iraqi Kurdistan. Until recently, research done by WADI showed an over 60 percent prevalence of FGM in the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq. This summer, Kurdish scientists published new figures that seem to imply smaller numbers of young girls are touched by it, with their percentage down to about 35.

Scientific data is hardly available in post-war Iraq. The Kurdish Higher Commission of Women Affairs has announced it will start new and extensive research by the end of this year.

Changing trend

The trend to change is the result of many years of campaigning, says WADI project coordinator Falah Murad. "We started awareness campaigns in 2004, but until very recently even the government was denying that in some villages 100 percent of the women were circumcised." Their advocacy resulted in 2011 in a law prohibiting the practice, but Murad says that hardly anything has been done since to implement it.

He is sure that the drop in the figures is mostly thanks to WADI visiting isolated villages like Twtakal. Over the years his people went to hundreds of them, showing a special movie and talking to the people about FGM. In six carefully chosen villages the policy has been refined. Aid workers are in close contact with the villagers and offer their assistance on other issues. They helped Twtakal to get a primary school and electricity. The message is clear: stop FGM and get services in return.

Yet WADI is fighting an uphill battle, as eradicating FGM does not only require a change of mentality, but also signals a clear break with traditions.

"First we could not believe that is was bad," say the women in Twtakal, "but then we saw the movie and we heard it is bad for women when giving birth, and for her sexual arousal."

Vying with tradition

While young boys at the door try to hear what is being said, the mokhtar's wife Nasrin recalls how her first daughter was only one year old when during her absence her grandmother took her to be circumcised. "For my second daughter I did not allow it because she was so afraid."

Islam was partly to blame, the women say, but even more is tradition, as it was done for generations. "The elder women were telling us that the prayers would not be accepted of girls who were not cut, and when they cooked their food would not be clean."

In a positive development, the local mullah, who was in favour of the practice, changed his tune after WADI started its visits. The women made vows to the aid workers not to touch their daughters. "Now we are each other's lawyers, we make sure none of us falls back to old habits," Nasrin says.

The midwife enters, a small woman in her 60s dressed in black, with a tattoo on her chin. Next to taking care of the births of the village's children, she used to circumcise the girls. "I would only cut a little bit." She folds a tiny piece of paper to show how it was done. "None of my girls died. They walked away afterwards."

Is it working?

She feels tricked by the organization, as she lost part of her income. "I thought they would pay me." She's threatening to pick up her old trade again, even though she knows it is now prohibited by law. "I am not afraid of the police," she said.

Aid workers admit that they have no way of making sure that no girls are circumcised, as they cannot examine them. That is the responsibility of the Kurdish government, they add, showing their frustration. "But we spent so much time with the villagers that we have built up a trust between us. The women promised to let us know if they hear of anyone doing it. And we have not been phoned."

They have a strong supporter in the mokhtar, who is happy about the change. Since Twtakal became a "Free FGM-village," between 10 to 12 girls have escaped the fate of circumcision. But more importantly, the village opened up to the world, children could get an education and Twtakal set an example for its neighbors.

"At first the other villages joked about Twtakal," says Falah Murad of WADI. "About the sign of an FGM Free Village, the change of old traditions. But then they saw the small services we provide, and the bigger ones by the government. Now other villages want that too. So now it's time for the government to pick this up."

Kak Sarhad is proud. The revolution started with his village, he says. "We have taken it to the forefront. We moved forward, we are more open-minded. I am happy it started from here."

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation