Female Circumcision Continues in Iraqi Kurdistan

SULAIMANIYAH, Iraq — Despite the efforts of Kurdish civil society organizations and the media to shed light on the practice of "female circumcision" — which is widespread in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq — this practice continues, albeit at a lower rate, in secret and with the blessing of some within the religious establishment.

By Miriam Ali

Although a number of nongovernmental organizations and activists have been working to put an end to female genital mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan, the practice continues in secret and with the blessing of some religious figures.

The Kurdistan parliament criminalized this practice in Article VI of the Domestic Violence Act of 2011.

Given the conservative nature of Kurdish society, it is very difficult to talk openly about issues pertaining to women and their bodies. When those in parliament were asked to discuss a law criminalizing female genital mutilation (FGM), talks were postponed several times due to the sensitivity of the issue. This resulted in the debate over this law lasting from 2006 to 2011.

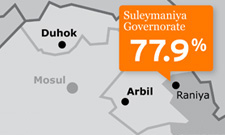

As a result of these efforts, female circumcision rates in all of Iraq fell by half, according to a report released by UNICEF in July 2013 addressing this practice in the 29 countries where it is most common.

The report noted that 8% of Iraqi women between the ages of 15 and 49 had been subjected to some form of FGM when they were young. The vast majority of these women are concentrated in the provinces of Erbil, Sulaimaniyah and Kirkuk.

In Iraqi Kurdistan, female circumcision is justified based on religious foundations as well as tribal traditions. Any attempts at enlightenment are resisted.

Adnan Ibrahim, a religious figure who rejects this practice, spoke to Al-Monitor about FGM. He noted that there is no relationship between female circumcision and Islamic teachings, and "there is no single piece of evidence in the Quran or sunna that legitimizes or calls for [female] circumcision."

He describes female circumcision as a "practice that results from ignorance or religious fervency." On the other hand, another religious figure, Sheikh Mohammed Hassan, told Al-Monitor, "I do not forbid the practice, based on sayings by the Prophet Muhammad that confirm [the legality of] female circumcision."

Muslims of various Islamic sects do not have a unified position on female circumcision, particularly within the Shafi school of jurisprudence, which accepts the practice. The vast majority of Muslims in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq belong to this sect. Moreover, Dar Al-Iftaa, the Egyptian educational institute founded to represent Islam, issued a fatwa condemning female circumcision on June 23.

Ehab Kharat, a psychologist from Erbil, told Al-Monitor, "[Female] circumcision is a historical-based crime that violates a woman's body. In the distant past, the practice was concentrated in the Nile Basin and Africa, yet under the guise of religion it began to seep into other countries. The practice involves cutting off active parts of the woman's body — parts that have a physical function. It is completely different from male circumcision. In the case of the latter, the flesh that is removed is not functional and does not have [a high concentration of] nerve endings. Yet, in the case of female circumcision, the most sensitive parts are removed. Thus, she loses the ability to obtain sexual satisfaction, yet her sexual desire does not decrease.”

Kharat notes that a distinction should be made between the idea of chastity and honor on the one hand, and sexual desire on the other. Female circumcision does not eliminate sexual desire — which is a psychological desire — but rather prevents a woman from obtaining sexual satisfaction. According to Kharat, it could even drive a woman to engage in deviant acts in an attempt to satisfy this psychological and physical deficit.

The long-term health consequences of this practice on women are not limited to mental health problems. Noor Suleiman, a doctor specializing in women's health, told Al-Monitor that the majority of circumcised women suffer from chronic health problems. Suleiman noted, "The tragedy begins with this primitive practice itself, which is usually carried out by one of the village elders. The latter typically has no [medical] proficiency and doesn't take into account the amount [of flesh] removed, the cleanliness of the tools being used or the overall health status of the girl. All forms of female circumcision lead to complications, the most serious being bleeding to death."

Suleiman outlines the health problems circumcised women face: "Nervous shock, damage to neighboring organs, inflammation, organ mutilation, infertility, difficulty giving birth, dysmenorrhea, a general risk of wounds and injuries to the Bartholin's glands."

Al-Monitor spoke to Falah Muradkhan, project coordinator at the Wadi Organization, a German-Iraqi nongovernmental organization focusing on human rights and family issues, which has been working in Iraqi Kurdistan for 18 years. Muradkhan said, "We have been working on awareness campaigns to condemn female circumcision for nine years. This is done through media coverage and our on-the-ground teams. Our efforts involve drawing attention to the harm and damage this practice can cause as well as providing first aid to circumcised women. We meet with those who perform these circumcisions and with religious figures and try to help them understand the danger of this practice, to deter them from facilitating it. We distributed 80,000 awareness pamphlets in the villages and cities of Iraqi Kurdistan as well as copies of our organization's newsletter, called 'Women's Rights.'"

Muradkhan referred to the results of a study conducted by the Wadi Organization in Kirkuk in 2012, as a model for the rest of Iraq. The study revealed that 38.2% of females over 14 years of age had been circumcised. Among those surveyed, 65% were Kurdish women, 26% were Arab and 12% were Turkmen. Muradkhan said that he is in contact with a female doctor in Diwaniyah who has evidence that there are cases of female circumcision in southern Iraq.

"We are working on a campaign called Stop FGM, to put an end to female circumcision in the Middle East — in Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Moreover, we are publishing data from recently conducted surveys," Muradkhan added.

Many circumcised girls abstain from talking to the media. Sana (not her real name), 39, said that she is trying to forget the experience. However, she is forced to deal with it in her marital life, and as a result the psychological damage it has caused. She noted, "I had no choice in the matter. My parents committed this crime against me when I was a young girl. Today, however, I am a married woman with children. Discussing this issue has become impossible."

Muradkhan recalls a number of incidents he witnessed during his work at the Wadi Organization. "I remember a father who approached me, and his eyes were filled with tears. He was distraught that he had his daughter circumcised a month prior. He would not have done this had the awareness campaign team come to the village a month earlier, because he realized the harm and risks of this procedure."

He continued, "Female circumcision causes innumerable problems. We have noticed that Kurdish men usually prefer to marry women from other ethnic groups, because there is a prevailing notion that Kurdish women are 'cold,' when it comes to marital relations. There have been many cases of young men who marry, only to end the relationship when they discovered the wife was circumcised. Problems related to 'coldness' between husband and wife as well as depression can lead to illness and suicide."

A report issued by Human Rights Watch said that FGM is practiced mainly by Kurds in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

Since 2003, the United Nations has designated Feb. 6 to be the international day against FGM.

Miriam Ali is a journalist who has worked with a number of Iraqi media outlets. She is an activist in the field of women's rights and has participated in a number of courses and workshops for promoting civil action.

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation