The Uneasy Fight Against FGM in Kurdistan

A campaign to stop Female Genital Mutilation

By: Suad Abdulrahman

On the 25th of November 2010, for the first time in history, a political leader in the Middle East acknowledged that female circumcision is a serious problem in his country. He added: “The presence of this practice is dangerous and should not be tolerated.” It was the Kurdish Prime Minister Barham Salih. This statement is a commendable and important step. However, it took years of activism, campaigning and exertion of pressure on the government to reach that point.

Six years ago, in a small office and with only a handful of employees, our organization “Wadi” decided to make efforts in every way possible to fight this barbaric “tradition”. The decision came after a survey performed by one of our regional teams in 40 villages in southern Iraqi Kurdistan: 902 cases of FGM were recorded from a total of 1534 women interviewed.

We worked on the ground spreading awareness about the physical and psychological harms of FGM, and at the same time we reached out to the media and tried to make FGM in Kurdistan a public and political issue. When our efforts to form a region-wide initiative started bearing fruit, we announced the movement in 2007. “Stop FGM in Kurdistan” , together with many other activists and women’s organizations, collected thousands of signatures, submitted a law to prohibit the practice and formed a media committee with representatives of many newspapers and radio stations. The campaign initiated extensive international and local media coverage and support.

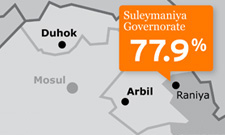

In January 2010, Wadi issued a comprehensive study on FGM and proved an average FGM rate of more than 72% in Iraqi Kurdistan (except the far northern Duhok region where it seems to be almost non-existent). In June, Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a special report on the issue. From that date on, FGM in Kurdistan became a major subject. The former taboo had given way to a lively public debate, and nowadays at least urban people are really concerned. This atmosphere ultimately caused the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) presidency to issue such a statement.

When we started working on female genital mutilation, we began to appeal for support and cooperation from the KRG and its related agencies. We visited the different ministries time and again, including Human Rights, Women, Youth, Culture and Social Affairs, without any outcome. From the huge budget allocated for the recovery and rebuilding process of northern Iraq, not a single penny has been spent so far for combating FGM. All our work has been realized by means of limited foreign aid provided by some NGOs and lately the Dutch embassy and the British Consulate. When requesting financial support from the NGOs, we always felt embarrassed as Kurds that such an important project in the region receives no support from any official governmental body, and the only backup we get is from people, organizations and countries thousands of miles away on the other side of the globe.

As an organization which is actively pushing this campaign, we have been confronted with defamations, accusations and suspicions. Our work has always faced fierce opposition, from the early days. The attackers came from different backgrounds and included religions men, conservative people, ignorant ministers, party-affiliated women’s rights groups, nationalists who thought that this issue brings shame to the Kurds, unprofessional media and many other agencies. In 2008, the Kurdish Parliament shied away from discussing FGM in the parliament. Even after the publication of the HRW report, instead of handling the issue in a professional way, many negative and baseless statements were made by several official and unofficial Kurdish bodies and bureaus that further highlighted and accentuated the poor treatment of this problem in Iraqi Kurdistan. For example, Mariwan Naqishbandy, the former spokesman for the Ministry of Islamic Affairs, said:

“The HRW report is a humiliation to the Kurdish society; and the Ministry of Affairs does not tolerate such an act under any circumstances. Not even 50 cases of FGM exist in Kurdistan, and the practice is only seen in certain regions.”

The same gentleman told Global Post: “This report from HRW is a fabrication”.

A Kurdish physician named Atiya told the same site: “FGM is nothing, and it has no negative mental consequences or harmful effects on the relationship between husbands and wives”. Another activist said: “I don’t know where they get these data from, perhaps they did their study in a remote village. We are currently doing a study, and when it is finished we will answer them” .

Many other interviews and statements of this kind were made, but for what end? After the KRG president had given his speech, everyone turned 180 degrees in their opinions. Nobody has continued to claim that we are distorting the facts, that we are liars, or that we busy ourselves with nonsense.

Unfortunately, there is now another game in town: the game of competing for who was the first to work on this issue, which one was the most active organization or agency, who has the best data, who is the hero of this field. Once again we are unfit for this sort of play and struggle, that is why we distanced ourselves from this tumult and withdrew from the “No to Female Genital Mutilation” platform which we initially worked to establish. We decided to rely on our strengths, pursue our field work actively and avoid trivial arguments.

Our teams come regularly to the villages, gather all the women, check the situation in the village, give medical advice and first aid etc.

Many taking part in these struggles have never dealt with FGM on the ground. They have never heard the cries of the victims. This abhorrent practice leaves such a permanent mark on the bodies and minds of girls and women that it is beyond description. While writing this paper, our colleague Shanga, who is an active participant in our organization, told me the story of a friend of hers who was forcibly cut by her relatives. She said:

“I was 4 years of age when I saw that they gathered all the children around and took them into one of the houses. I fled away and didn’t want to go back home again, but they followed me and forcibly took me with kicks and blows to the place where the other children were cut. There was blood all over, and they forcibly circumcised me, too. I felt an intense physical pain which I still feel. I suffered great mental anguish and I will never forget what happened. I don’t understand why did they do what they did. When I sit with my friends and each one retells the story of her circumcision, I feel that we share the same experience, that we all bear an endless wound.”

This is only one story among thousands of similar tales that shake every living conscience.

The end of 2010 witnessed a confession about the existence of FGM in Kurdistan, but the real confrontation might not have begun yet. The KRG president gave green light for anti-FGM activities and endorsed combatting the practice. According to the latest report from the Ministry of Health, from a total of 5112 women and girls of all ages and social statuses, 41% were circumcised. This is the first official statistic worth mentioning. On another level, many promises were made to start campaigns and mobilization of human and financial resources to confront the practice in Kurdistan.

However, from the religious angle – which is the most important motive for the practice – no fatwa has been issued yet to prohibit FGM. Stating that FGM is not a religious duty is clearly not sufficient. Clerics have a huge moral obligation to dissuade people from FGM because their word is so highly regarded by many. Yet those mullahs who still support the practice and encourage its continuity can go on without being punished. There is still no law in Kurdistan or Iraq or any other Middle Eastern country that prohibits FGM, and this fact may reduce all the promises and efforts to insignificance and thwart any serious step towards eliminating the practice.

Suad Abdulrahman is a project coordinator with the Association for Crisis Assistance and Development Co-operation (WADI) in Iraqi Kurdistan. She is also a spokesperson of the campaign “Stop FGM in Kurdistan”.