Iraqi Kurdistan: Law Banning FGM Not Being Enforced

One Year After Landmark Bill, Harmful Practice Persists

(Erbil) – The practice of female genital mutilation continues in the Kurdistan region of Iraq a year after a landmark law banning it went into effect because the Kurdistan Regional Government has not taken steps to implement the law. The Family Violence Law, which went into effect on August 11, 2011, includes several provisions to eradicate female genital mutilation (FGM), recognized internationally as a form of violence against women.

The regional government has begun to run awareness campaigns, train judges, and issue orders to police on the articles of the law dealing with domestic violence. But it apparently has not taken similar steps to implement the FGM ban, Human Rights Watch found. Between late May and mid-August, 2012, Human Rights Watch spoke with over 60 villagers, policemen, government officials, lawyers, and human rights workers in the districts of Chamachamal, Choman, Erbil, Penjwin, Pishdar, Rania, Soran, Shaqlawa, and Sulaimaniya about the problem.

“The KRG parliament took a huge step forward when it passed the Family Violence Law,” said Joe Stork, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “Authorities now need to begin the difficult process of putting a comprehensive plan in place to implement the law, including informing the public, police, and health professionals about the ban on FGM.”

In June 2010, Human Rights Watch issued an 81-page report, "They Took Me and Told Me Nothing: Female Genital Mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan," which urged the Kurdistan Regional Government, parliament, civil society, and donors to take steps to end the practice. The report described the experiences of young girls and women who undergo FGM and the terrible toll it takes on their physical and mental health. The KRG parliament passed the Family Violence Law in June 2011.

In the recent interviews, Human Rights Watch spoke with more than 20 villagers who had daughters in the age range when FGM is traditionally performed – between ages 4 and 12. Some said they were no longer intending to have the procedure performed on their daughters, as a result of awareness campaigns conducted by representatives of nongovernmental organizations who had visited their villages, but a few said they planned to have the procedure done. None had seen any action or awareness efforts by the government.

“Okay, so there’s a law now, so people don’t talk about it as much now, but if people in my village or another village want to have it done to their girls, they can easily still do it secretly,” said a woman from Rania.

Several police officers told Human Rights Watch that their superiors had not given them any instructions or explanation of the ban on FGM. The head of an Interior Ministry directorate tasked with tracking violence against women confirmed to Human Rights Watch that no such instructions or explanation had yet been given.

The highest Muslim authority in Iraqi Kurdistan issued a fatwa in July 2010 saying that Islam does not require female genital mutilation. But after parliament passed the Family Violence Law, Mullah Ismael Sosaae, a religious leader, gave a Friday sermon in Erbil demanding that the KRG president, Massoud Barzani, refuse to sign it into law. Barzani did not sign it, but allowed the law to go into effect when it was published in the government’s Official Gazette (#132) on August 11, 2011. Critics in the Kurdish region say that this was an effort by Barzani to avoid confrontation with religious leaders like Sosaae while allowing the bill to become a law, but that this approach sent the message that those against the law could continue to undermine it.

Members of parliament and civil society activists have criticized the government’s lack of action, and say the practice remains prevalent, particularly in areas such as Rania, Haji Awa, and Qalat Diza.

“We don’t have a problem passing laws here in the KRG, but implementation is another matter entirely, especially when the law is controversial like this one,” Kwestan Abdullah, a member of the Women’s Affairs Committee in the KRG parliament, told Human Rights Watch. “The Family Violence Law, in almost all its aspects, has not yet begun to support women on the ground, and this is especially true of the FGM issue. Nothing is happening, and no one is even really talking about plans to implement it.”

The Kurdistan Regional Government should take concrete steps to enforce the law banning female genital mutilation, Human Rights Watch said. This should include providing training to police, courts, and regional officials to enforce the law.

So-called community midwives, women with no formal medical training but who help with births and also carry out FGM, are not licensed and so fall outside the Health Ministry’s purview. Any eradication effort would have to involve community midwives and should include helping them find alternative sources of income, Human Rights Watch said.

The Ministry for Endowments and Religious Affairs should include religious leaders in training and awareness-raising on the imperative to end violence against women and girls, including FGM, Human Rights Watch said. The ministry should include information about the July 2010 fatwa in all information and training sessions. A complaints mechanism should be established for people to inform the ministry when clerics continue to preach that FGM is a religious obligation.

For more detail from interviews with residents, groups working in the region and officials and other background, please see the below text.

Female Genital Mutilation and Its Prevalence in Iraqi Kurdistan

According to the World Health Organization, “Female genital mutilation (FGM) comprises all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.”Female genital mutilation violates the rights of women to life, health and bodily integrity, non-discrimination, and the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. In addition, since the practice predominantly affects girls under 18, it also violates children’s rights to health, life, physical integrity, and non-discrimination.

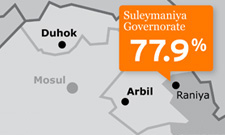

Before passage of the Family Violence Law, several studies by the government and one nongovernmental organization estimated that at least 40 percent of girls and women in Kurdistan were subjected to FGM, and in German, one area studied, the rate was over 80 percent. Shortly after the 2010 release of the Human Rights Watch report, the Kurdistan Health Ministry surveyed 5,000 women and girls and found that 41 percent had undergone the procedure, and that the practice is more prevalent in some regions than others.

WADI, a German human rights group that campaigns against FGM in Kurdistan, and the local women’s rights group PANA released a report in April 2012 that found that FGM is common and crosses ethnic lines in Kirkuk province, affecting 65.4 percent of Kurdish women, 25.7 percent of Arab women, and 12.3 percent of Turkoman women.

Lack of Official Action

“In general, the law has not been implemented,” Kurda Omar, head of the Interior Ministry’s Directorate to Follow Up on Violence Against Women, told Human Rights Watch on August 8. “So far we have printed out about 68 pamphlets and booklets related to the law and we have distributed this to our officers, also at schools and colleges, and we have provided training (for dealing with instances of domestic violence against women) for officers at our department. There is an order to hire about 100 people at our department and other agencies to deal with this and we are intending to hire mostly women.”

With regard to implementation of the FGM portion of the law, she said, the ministry had not given orders and instructions yet, but that at an August 8 meeting KRG Prime Minister Nichirwan Barzani, “insisted the law should be implemented.” She added that Barzani met with other agencies, including the Judicial Council, which is responsible for establishing special courts called for in the law.

“They think such a plan is not easy to achieve and will require very professional judges and employees,” she said, adding that people do not bring complaints regarding FGM but that, “If someone would see or hear about this and report it to police, then police would address it.”

A police officer in Rania told Human Rights Watch on June 13 that his department has received no notification of the law or its implementation. “We know about the law because, when it passed last year, some of the media mentioned it,” this officer said. “I don’t really know what it restricts. We have no orders at all about the law.”

On June 25, a police officer in Sulaimaniya told Human Rights Watch: “We have been told there are new orders to arrest men who beat their wives badly because this law was passed, but we have not heard anything about FGM.”

Human rights organizations operating in Iraqi Kurdistan say these responses are typical of their experiences as well.

The few judges and police commanders in Kurdistan who actually knew about the law from the government said they received no explanation or instructions on how to implement it.

Information Campaigns by Nongovernmental Groups

“There have been [government] awareness campaigns for other parts of the law, but not FGM, because the subject is taboo,” Falah Moradkhin, project coordinator for WADI, told Human Rights Watch. “There have been no publications or awareness campaigns by the Health or Education Ministries.

“If it will take some time to deal with the problem of FGM, we understand, but we don’t see the government doing anything. Midwives licensed by the Health Ministry haven’t been retrained and police aren’t given instructions to enforce the law.”

Tara Ali Arif, a lawyer with WOLA (Women’s Law Association), a woman’s legal aid association in Sulaimaniya, told Human Rights Watch, “It is a good law, but there is no real effort on the part of the government to implement it – not even the first stages.”

“The law says that women should be employed by police stations to help deal with the issue,” Arif said, referring to the domestic violence law generally. “Out of six police stations in Sulaimaniya we visited, none have received any orders to even look into hiring women.”

WADI’s Moradkhin told Human Rights Watch that the current situation may only be driving the practice underground. He said, “It used to be much easier to get women to speak about FGM,” he said. “We often find that, after we tell them FGM is now illegal, they become nervous about admitting it. Even if a woman tells us she had FGM performed on her daughter, she will not tell us who did it anymore.” Even in areas where villagers were openly defiant of the law just after it was passed, the practice appears to now be performed in more secrecy than before, he said.

Amina Rasoul Moussa, head of a rural chapter of the Kurdistan Women’s Union, confirmed that the practice has become more secretive, but said that FGM is still commonly practiced in more traditional areas. “When we get details of a woman who is still performing FGM from families who take their daughters to her, we visit her to ask about it,” she told Human Rights Watch. “She and her neighbors will all deny it, and then there is nothing more we can do. We aren’t the police. People don’t feel the police will investigate this unless it is out in the open, so now many just stop talking about FGM, but don’t stop doing it.”

Interviews with Villagers

Villagers who spoke with Human Rights Watch attributed their knowledge of the law to nongovernmental groups whose representatives have visited them as part of FGM awareness campaigns. They said without exception that they had little or no expectation of legal consequences.

“Okay, so there’s a law now, so people don’t talk about it as much now, but if people in my village or another village want to have it done to their girls, they can easily still do it secretly,” said a woman from Rania. “There is no thought that they will be punished because there is no talk about it on television or by the police. The only ones talking publicly about it are the mullahs, who are against the law.”

Some women indicated that a government campaign would affect their decisions about FGM.

“The NGOs come and tell us this [FGM] is bad for our girls, but the religious leaders have always told us it is good for them,” a woman from Pishdar told Human Rights Watch. “Who should we believe?” When asked if the law banning FGM affected her decision, she said, “The NGOs tell us that it is against the law, but we do not hear this from anyone but them.”

A woman from Rania told Human Rights Watch that she had not decided whether she would take her daughter to a local midwife who performs FGM. “Deep in my heart, I do not want to do this, but so many people are telling us that it is important to continue our tradition,” she said. “Until now, I have not heard anything from the government. Now I cannot decide, but if someone from the government comes to tell us it is prohibited and explain it to us, maybe this would support me in keeping my daughter from having this done to her.”

Another woman from Rania told Human Rights Watch that she had not had FGM performed on her two daughters, but keeps this a secret from her neighbors and extended family. “I do not want everyone to talk and make problems for me with neighbors or religious leaders,” she said.

On June 9, Human Rights Watch attended an educational seminar about the Family Violence Law for local women in Haji Awa, one of the areas where residents were most outspoken against the FGM ban when the law passed. The event was co-sponsored by WADI and the Kurdistan Women’s Union. Judging by their questions, such as whether practices like forced or underage marriages, domestic violence, and FGM were legal or not, the women attending had almost no idea about the law and were hearing its details for the first time.

Human Rights Watch found indications that some midwives who have practiced FGM on girls have stopped doing so in several areas after nongovernmental organizations there told them about the law, though the silence surrounding the issue makes this difficult to confirm.

On June 14, a woman from Pishdar told Human Rights Watch, “If I want to take my daughter to have this [FGM] done, I do not know of a traditional woman who will do it here now. I would have to go into Rania or another area.”

Religious Opposition to the FGM Ban

On July 6, 2010, shortly after the release of the June 2010 Human Rights Watch's report on FGM, the High Committee for Issuing Fatwas at the Kurdistan Islamic Scholars Union, the highest Muslim religious authority on religious pronouncements and rulings, issued a fatwa, or religious edict, stating that FGM predates Islam and is not required by it. The fatwa did not explicitly ban the practice but encouraged parents not to subject their daughters to the procedure because of the negative health consequences. However, because villagers only heard about the fatwa from the campaigns by nongovernmental organizations, some said they doubted its veracity and so were not dissuaded from having FGM performed on their daughters.

People in Iraqi Kurdistan with whom Human Rights Watch spoke between May and August were nearly unanimous that opposition by religious leaders was the main obstacle toward implementation of the Family Violence Law, and that their future support would be the key to its success. But as one human rights activist noted, “Religious leaders all receive their salaries from by the government, so the government cannot say it is powerless to influence them.”

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation