FGM remains a problem in Iraqi Kurdistan and beyond

While much research exists on the prevalence of FGM in Africa, “the existence of FGM/C in the Middle East is less known,” according to IRIN humanitarian news and analysis, a service of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs [1]. One region that is thought to have a high rate of FGM is Iraqi Kurdistan, an “autonomously governed region within the state of Iraq” [2]. Iraqi Kurdistan, in northern Iraq, is a region of five million people and is a “deeply traditional and often tribal society” [3].

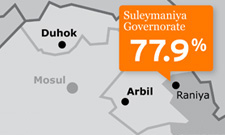

A survey conducted in 2009 by the Kurdistan Regional Government’s Human Rights Ministry found that 40 percent of females in the Chamchamal area between Kirkuk and Sulaimaniya were FGM victims. However, a different study by The Association for Crisis Assistance and Development Cooperation (WADI) a German-Iraqi NGO, which covered a broad area between Irbil, Sulaimaniya and Kirkuk, found that more than 70 percent of those in the study were FGM victims [3]. The highest percentage of FGM was in Garmyan, a largely rural area where 81 percent of the females surveyed were FGM victims [4]. According to a 2010 BBC article, “there are no comprehensive statistics, but a number of recent surveys have shown it to be surprisingly widespread” [3].

An even more recent study by WADI shows that FGM may actually be widespread in Iraq beyond the Kurdish region. According to this study, which involved more than 1,200 women, nearly 40 percent of women in the Kirkuk region are FGM victims, a region where FGM was not thought to be practiced. According to WADI, “The data from Kirkuk are an indication for the assumption that genital mutilation is widespread throughout Iraq. Millions of women and girls are likely to be affected by this grave human rights violation” [5].

This is despite the fact that Iraq has signed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), all of which “place responsibility and accountability on the Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Regional Government for any human rights violations that take place in Iraqi Kurdistan, including FGM” [2].

FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan is usually performed on girls between 3 and 12 years old [2]. It is often performed in unhygienic conditions, and girls are often taken by female relatives to have FGM performed [3]. Some girls are told they are going to visit a relative or attend a party [2]. According to the June 2010 Human Rights Watch Report, “girls are often unaware what is about to happen to them, they experience great pain during the procedure and afterwards, and the practice can have lasting physical, sexual and psychological health consequences” [2]. As a 17-year-old girl from Iraqi Kurdistan recalled, “I remember my mother and her sister-in-law took us two girls, and there were four other girls. We went to Sarkapkan for the procedure. They put us in the bathroom, held our legs open, and cut something. They did it one by one with no anesthetics. I was afraid, but endured the pain. There was nothing they did for us to soothe the pain. I had one week of pain. After that just a little bit. I never went to the doctors. [They were] never concerned. I have lots of pain in this specific area they cut when I menstruate” [qtd. in 2].

Another woman from Iraqi Kurdistan, named Dashty, was told by her mother that they were expecting company. Rather than friends like Dashty expected, however, a midwife came to the house and performed FGM on Dashty, after her mother beat her for resisting and other women held her down. As Dashty explains, “Since that day, my personality has changed and I’m depressed. …I’ve lost my love for this world because of what happened at the hands of people I trusted” [2]. After FGM is performed, the midwife often covers the wound with ashes from the tanoor, “a flat-surfaced oven used to bake traditional bread.” Midwives from Iraqi Kurdistan claim that this helps the wound to heal faster [2].

A February 2010 article from the Institute of War & Peace Reporting mentions Mariam Nadr, a 77-year-old woman in the upscale neighborhood of Erbil, in Iraqi Kurdinstan. She is a prominent and respected member of society, one reason being that she was an FGM practitioner for many years [4]. As Nadr explained, “No one told me mutilation is bad; I did it for the sake of religion,” [qtd. in 4]. For many women in Iraqi Kurdistan, FGM is “a cultural and religious rite” [4].

According to a June 2010 BBC article, “female circumcision is virtually unknown in the rest of Iraq, and it is not clear why it seems to have taken root in Iraqi Kurdistan” [3].

And according to the Human Rights Watch report, there are many reasons that the people of Iraqi Kurdistan practice FGM, from defending it as Islamic sunnah, which is “a non-obligatory action to strengthen one’s religion” and saying that FGM is necessary to “preserve cultural identity,” to saying that the practice of FGM is related to social pressure and the idea that girls must be “circumcised” to be “marriageable and respectable members of society.” Some even said that hot climates like those of Iraqi Kurdistan necessitated that female sexuality be controlled [2]. Explains one Iraqi Kurdish woman, Ameena F., “It is sunnah…. Everyone is doing this. Of course this is a

good thing for my daughter. When someone does something, we all have to do it” [qtd. in 2]. The Human Rights Watch report asserts that the exact origins of FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan are not known and that “the practice may have been a traditional custom and a religious justification may have been later added” [2].

While FGM has no specific Islamic origins, “some clerics in Kurdistan have welcomed it because they believe it stifles sexual urges in young girls and women” [3]. Echoes a Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty article from 2009, some supporters of FGM in Kurdish Iraq believes the practice makes women “clean” and controls their sexual desires. Food that has been prepared by women who have not undergone FGM can actually be considered unacceptable [6]. The Human Rights Watch report tells the story of one woman whose marriage was declared haram (forbidden) by her sister-in-law after she discovered that her brother had been eating food cooked by an “uncircumcised” woman, which she considered dirty. Soon after this discovery, a midwife performed FGM on this woman [2].

While globally, the majority of Muslims do not practice FGM, many in Iraqi Kurdistan cite religion as their reason for practicing FGM [2]. According to the earlier WADI study, 84 percent of those surveyed cited religion as the reason they practice FGM. Since the 1970s, local mosques would use loudspeakers to encourage families to FGM during the months of March and April [4]. According to Thomas Von Der Osten-Sacken, the director of WADI, FGM is obligatory according to the Shafii Islamic school that most Iraqi and Iranian Kurds belong to [6]. He explains, “We found that wherever you have the Shaafi school of law, female genital mutilation is extremely widespread. That might be also one the reasons why you can’t find it so much in Turkey or Syria’s Kurdish communities — because they’re mostly Hanafi” [qtd. in 6]. Despite this, “research shows the custom preceded Kurdistan’s conversion to Islam and Islamic leaders have disavowed any connection” [4].

Because so many cite religion as a reason they practice FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan, WADI believes “mullahs can help bring its cause to the public” [4]. According to Dr. Basher Khalil al-Hadad, the mullah of the largest mosque, “Since most of the people who practice FGM say it is because of religion, I think it is our duty to talk to people about it” [qtd. in 4]. Hadad clarified that Islam does not advocate for the practice of FGM. “The Holy Koran has not ordered females to be circumcised and there is no strong hadith (saying of the Prophet Muhammad) that says females should be mutilated in this way,” he said [qtd. in 4].

FGM in areas like Iraqi Kurdistan can be particularly dangerous, due to lack of access to emergency healthcare. As the Human Rights Watch report explains, “The lack of health care, particularly emergency care, makes FGM—always unsafe— a potential death sentence in Kurdistan” [2]. Also, one recent study, which showed that victims of FGM are more prone to mental disorders, was conducted among a group of 79 Kurdish girls, 8-14 years-old, in northern Iraq. The study found that cases of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and somatic disturbances were very high among these FGM victims, up to seven times more common than in girls in the same region who had not undergone FGM [1].

The Human Rights Watch report is especially critical of the Kurdistan Regional Government’s relative inaction on the issue of FGM. According to the report, “although it has not been completely inactive, its efforts have been piecemeal, low key and poorly sustained” [2]. In 2007, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s Justice Ministry issued an order that FGM practitioners should be arrested, but according to Human Rights Watch, this was apparently never enforced [2]. This is evidence, according to Human Rights Watch, that not only were the small steps taken by previous administrations not built on, but that in 2007 “the former government’s commitment appeared to falter” [2]. In 2009, the Ministry of Health in Kurdistan “developed a comprehensive anti-FGM strategy in collaboration with an NGO,” only to later withdraw its support of the project and accuse the NGO of harming Kurdistan’s reputation [2]. Human Rights Watch also cites the Kurdistan government’s failure to systematically collect statistics on FGM as a major problem [2].

Explained Nadya Khalife, who wrote a Human Rights Watch report on FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan, “Eradicating it in Iraqi Kurdistan will require strong and dedicated leadership on the part of the regional government, including a clear message that FGM will no longer be tolerated” [qtd. in 3]. The report itself echoes that government action is the most important step towards eliminating FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan, explaining that there is a need for “Iraqi Kurds in positions of leadership and influence to recognize and accept that FGM is a problem, one that can be addressed through concerted action that will reinforce Iraqi Kurdistan’s reputation as a society committed to the protection of the rights of women and children, and a society in which Muslims practice their faith without FGM, as is the case with the majority of Muslims across the world” [2].

The Kurdish government does tend to be progressive on women’s rights issues. For instance, it has enacted measures to combat domestic violence, as well as laws prohibiting reduced sentences for honor killings, a rarity in the region. It also has a legal quota of 30 percent for women in the legislature [2]. While the Kurdish government does tend to be progressive on women’s rights issues, however, “it has not addressed FGM in a systematic way” [7]. While the majority of the Kurdistan National Assembly supported an FGM ban in 2008, the ban never became a law, and “the current government has taken no actions to stop the practice” [7]. As Jessie Graham of Human Rights Watch explained, “It’s dangerous, it really interferes with the quality of women’s lives, it’s something that can have lasting health effects, both mentally and physically. So they need to come out against it and say this isn’t a religious practice, this isn’t a traditional practice that we need to hold onto” [qtd. in 7].

According to the Human Rights Watch report, the eradication of FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan will require “strong leadership from the authorities and partnerships across the political spectrum and with religious leaders, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and communities to bring about social change” [2]. Influential members of Kurdish society, including “religious leaders, healthcare workers, teachers and community leaders,” need to promote debate about FGM within local communities. This debate should be stimulated and sustained multilaterally, by local authorities, NGOs and other channels [2]. Von Der Osten-Sacken of Wadi agrees that a multilateral approach to ending FGM is critical, involving the government, “the government, NGOs, the United Nations and the religious establishment to combat the practice” [4]. According to Von Der Osten-Sacken, “If we all together start an organised campaign, in five or six years, we will end FGM in Kurdistan” [qtd. in 4]. According to Zahibi, education and raising awareness of women’s rights issues are essential in the fight against FGM [6]. As she explained, “Many educated men and women — after getting married — they don’t let their daughters be circumcised. So fortunately it is decreasing here” [qtd. in [6].

Progress is slow but seems evident in Iraqi Kurdistan. According to the February 2010 article from the Institute of War & Peace Reporting, “Change has come slowly, and Iraqi Kurdistan remains a battleground where education and awareness campaigns must overturn centuries of ingrained tradition” [4]. According to the earlier WADI study, age discrepancies among those who practice and those who do not practice FGM seems to be evidence that “the practice is falling out of favour with younger parents” [4]. Women under the age of 20 had an FGM rate of 57 percent, women between 30 and 39 years old had an FGM rate of 74 percent and women in the age bracket of Nadr, the prominent FGM practitioner, have an FGM rate of almost 96 percent. According to a Wadi press statement on the study, “The study shows a clear correlation between the level of education and the attitudes towards FGM” [4]. Von Der Osten-Sacken and Zahibi agree that attitudes toward FGM are slowly changing in Kurdish areas. According to Von Der Osten-Sacken, the anti-FGM movement is gaining momentum especially among “young people, Kurdish intellectuals, and some politicians in Iraqi Kurdistan” [6].

In the June 2010 Human Rights Watch report, a Kurdish woman named Khanm, who underwent FGM when she was a young girl, also had two of her own daughters “circumcised.” She will not, however, have the procedure performed on her two youngest daughters. As she explained, “For the first two, all my friends and neighbors were insisting that I do it. […] This was the normal practice before, but now things are changing” [qtd. in 2].

For sources, click “More.”

[1]

“IRAQ: New research highlights link between FGM/C and mental disorders.” IRIN. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 13 January 2012.

<http://www.irinnews.org/Report/94638/IRAQ-New-research-highlights-link-between-FGM-C-and-mental-disorders>.

[2]

“They Took Me and Told Me Nothing: Female Genital Mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan.” Human Rights Watch. June 2010.

<http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/06/16/they-took-me-and-told-me-nothing-0>.

[3]

Muir, Jim. “HRW presses Iraqi Kurds to ban female circumcision.” BBC News. 16 June 2010. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10327619>.

[4]

“Female Circumcision Ban Urged: New survey reveals that majority of women in Kurdistan have undergone genital mutilation.” Institute for War & Peace Reporting. ICR Issue 323. 11 February 2010. <http://iwpr.net/report-news/female-circumcision-ban-urged>.

[5]

“FGM in Iraq is more widespread than thought.” Desert Flower Foundation. 12 April 2012. <http://www.desertflowerfoundation.org/en/fgm-in-iraq-is-more-widespread-than-thought/>.

[6]

Esfandiari, Golnaz. “Female Genital Mutilation Said To Be Widespread In Iraq’s, Iran’s Kurdistan.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 10 March 2009. <http://www.rferl.org/content/Female_Genital_Mutilation_Said_To_Be_

Widespread_In_Iraqs_Irans_Kurdistan/1507621.html>.

[7]

“Fighting FGM in Northern Iraq.” Public Radio International. 21 June 2010. <http://www.pri.org/stories/business/nonprofits/fighting-fgm-in-northern-iraq2052.html>.

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation