Ms. Arian Arif – a woman's strength cannot be hidden

By Haje Keli

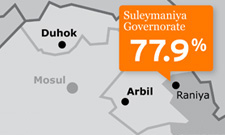

If you entered a room full of women, she would instantly be the one who captures your attention. Young, charismatic, and with a disarming, contagious smile, Arian Arif comes across as one who must have attended a prestigious university and lived most of her life in the West. One would never imagine that this 31- year old journalist left Kurdistan just 3 years ago – she completed her studies in Sulaymaniyah until finding love with a Kurdish man living in Norway. Born in Sulaymaniyah, Ms. Arif previously taught mathematics at a grade school level and worked in a number of ministries before her journalistic talent was discovered by the mother of Kurdish politician, Dr. Barham Salih.

“It was my only wish in this life to live and die in Kurdistan, and only leave for vacations. Fate would have it different – I left Kurdistan because I fell in love with a man in Norway.” She continues furiously, “People think that living in Norway has made me conscious about women’s issues and that it’s because I’m outside my homeland that I speak my mind about women’s rights in Kurdistan. They could not be more wrong; in fact, I am less active here than I ever was in Kurdistan.”

In Kurdistan, Ms. Arif wrote articles for several well-known Kurdish newspapers. Her articles were primarily about women and the various obstacles they face. One women’s issue, in particular, that drew her attention the most was female genital mutilation, also commonly referred to as female circumcision.

Debating female genital mutilation is still something of a taboo issue in Kurdistan, but certain people, including Ms. Arif, and some groups such as the German-based Association for Crisis Assistance and Development Cooperation, or WADI, work hard to try to spread awareness of this horrible practice despite meeting resistance from many sides. Although focus on this topic in Kurdistan and elsewhere has increased over the last 7-8 years, Ms. Arif’s unfortunate introduction to this practice came much earlier.

The day

Ms. Arif’s father owned an ice cream shop and wished to expand his business. He moved his family from Sulaymaniyah to Raniya in order to set up a business there. She explains the tragedy that would soon follow in her own words:

“I was nine and the women in the neighborhood had a great deal of impact on my mother. They asked her if she’d circumcised her daughters. ‘How could you not?’ they asked. ‘You really have to. Badji Gole is going to circumcise our daughters tomorrow.’ Two of my friends, two beautiful sisters, were scheduled for Badji Gole’s ‘operation’ as well.

“Another friend, Ala, was also facing the same fate as us, but when her mother took her hand to take her to Badji Gole, her older sisters refused to let her go. They shouted at their mother, saying that Ala should not go through this. Ala was off the hook. Our laundry room was used as the operation room. Without telling us what would happen, they took us to the laundry room and held a hand over our mouths. In the room, we saw an old wrinkly woman with tattoos all over her face. We saw plastic covers on the floor and a collection of razors. We were all so young, our eyes were so full of life and joy and with those razors Badji Gole took all that away. Our mother put us in the hands of an old, tired woman with shaky hands to play with our bodies and mess with what God had created. It’s only by the grace of God we survived her cuts. My mother was illiterate, and so were all the other women. They kept us down with force. Every little girl in there wanted the other girls to go first. The two sisters who were my friends, Ajin and Jino were beside me. Ajin seemed to know what was going to happen. She said her cousin had gone through this a few weeks ago and she had said how much it hurts. The first girl to be cut was three years old. I remember my mother asking Badji Gole not to cut me very deep. Badji Gole replied that the more she cuts of my genitals, the more the blessing (kheyir) there is.”

A big why arose in Ms. Arif’s heart that day. This question still haunts her – a question for herself, her parents, and Badji Gole. She says she knows on a factual level why parents do this to their daughters, but the young child in her is not satisfied with that as an answer.

They put Ms. Arif in bed and she recalls cursing at her mother and the woman who mutilated her. “I was so devastated that it made me hate my mother,” she said. “This pain made me hate the most precious person in my life. At that moment, everything was mother’s fault.”

Ms. Arif doubts that this particular phenomenon can be labeled as purely the fault of men. “My father was not home when they mutilated me,” she said. “When he came home and found out what had been done to me, he got very angry with my mother and called her irrational.”

Ms. Arif vividly remembers the rest of the day. “They surrounded us with cookies, chocolate and potato chips as if that would heal our unbelievable pain. They placed all us girls in the far back room of our house. We were the shame of the neighborhood and we had to be hidden away. No one ever spoke of our mutilation. They were ashamed of us and our genitals. When my brothers were circumcised, they received countless gifts and words of praise and blessing from people. They had visitors and yet all they did for us was some candy and a few mattresses on a cold floor. “

This, Ms. Arif claims, is why she will no longer keep quiet about her genital mutilation. She is emerging from hiding, from that back room, and into the light. She is doing it for Ajin, Jino and every other girl who was mutilated and for those who will unfortunately face genital mutilation. The world needs to hear Ms. Arif’s story and now they finally are. This, she says, will set her apart from the woman who circumcised her. If she continues to hide and live in shame, she will keep Badji Gole’s horrific actions alive and well.

As for the alleged religious nature of this mutilation, Ms. Arif says, “There nothing in any religion claiming that women should be circumcised. Yet we see that this practice exists among different cultures belonging to different religions.”

Life after mutilation

When asking Ms. Arif about her life as a teenager and after,she is very frank: “I enjoyed attention from boys, but I never saw it as anything else than words. I never thought love was anything other than words, it could not be physical.” When Ms. Arif was eleven, she was in an accident that left her seriously injured, and she had to go through 8 surgeries to recover fully. That, in addition to her genital mutilation, made falling in love and finding a suitable man difficult. When Ms. Arif was nineteen, she befriended a man with a similar mindset and way of thinking. Their friendship grew deeper, and she eventually tried telling him about what had happened to her. He stopped her in the middle of her sentence and said that anything she had gone through did not matter to him because she was perfect. Time went by and her friend moved abroad. From there he seemed to change, and brought up what she had once tried to tell him. She finished the story of the two incidents from her childhood that had scarred her for life. He replied by saying that she probably looks horrible. Many more incidents like these would occur until Ms. Arif found the man who would be her husband.

Ms. Arif’s experience made her aware that members of the opposite sex may not accept her for who she is, and be unable to look past horrible things that had happened to her. Many men would be captivated by her looks and immense charm and glow, but as soon as Ms. Arif opened up about her past, they withdrew. She said, “I believed in myself, and I knew what a good person I was. I can’t do anything about it if other people do not see that.”

There was a man that did not let Ms. Arif’s past overshadow the magnificent person that she is. Ms. Arif calls him the very definition of respect and love. “His love and respect for women is mind-blowing. I want to tell the world how wonderful he is. I owe him so much. There are many Kurdish women who never experience or ask for an orgasm because of the taboos in our culture. Luckily, I am with a man who understands and caters to my mental and physical needs. He is the best friend and lover. He is making up for the damages happened to me, he is my calmness and safety.“

Laws and actions against FGM in KRG

Ms. Arif wants female genital mutilation to be outlawed in Kurdistan. She also wants women who were subjected to FGM be treated physically and mentally. They should have teams of support tending to their needs. “I married a wonderful man who understands me. What about all the women who do not have wonderful men and remain incomplete?” she asks.

She says she begs every member of the new parliament to ignore people who claim that genital mutilation is a thing of the past or a dying practice. “The Minister of Religious Endowments says female genital mutilation was a phase. How dare he? I challenge him and anyone who claims the same. What they are doing is mocking thousands of girls who are scarred for life. They put a sheet over the wounds of these girls and pretend they were never hurt. The [Kurdistan] government has a negative view of people who wish to draw attention to female genital mutilation. When I lived there, I was in a constant fight with people in power who disliked my interest in this issue. Do they really think that by turning a blind eye to this issue it will make our region look good?”

According to Ms. Arif, the numbers of mutilated women are higher than published reports state as there are women who do not wish to reveal that they have been circumcised: “I understand why they wish to keep quiet, they do not want to put their family’s name in shame. They have already lost a lot, and experienced psychological damage. On top of all of this, they keep it inside. It’s important to own our problems and be first in the line to speak about them. Women in our Kurdish culture are still too weak to speak about their own problems, and therefore, people keep oppressing us. They have to start questioning, why do people constantly hurt us? I proudly reveal my name and story in this article because women need to stand up and say, ‘Yes we have been genitally mutilated.’“

Ms. Arif says that her wish was to stay in Kurdistan for her whole life, but her husband has a life in Norway and she wanted to join him. In the cold Scandinavia, far from her homeland, she is not as able to speak, write and campaign against female genital mutilation. The language barrier and the difference in work culture frustrate her and she wishes she could be as active as she was in Kurdistan. Ironically, while many Kurdish women wish they had Ms. Arif’s life in Norway, she longs to return “home” and fight for her cause.

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation