Genital mutilation is traditional in Iraqi Kurdistan

Activists are seeking to end female genital mutilation in Iraq’s Kurdistan even as they try to determine how common the practice is.

By Nicholas Birch

SULAIMANIYAH, Kurdistan (WOMENSNEWS) -- With her six children and her fine-boned face aged beyond her 39 years, Amina Khidir seems a fairly ordinary Kurdish farmer’s wife. Unlike most, though, she also has a job. She circumcises girls.

"My mother taught me the technique," she says, sitting cross-legged in her house in Zurkan, a village in the remote Pizhdar district of northeastern Iraqi Kurdistan. "I took over three years ago, just before she died."

Her first operation, she remembers, was on her own daughter. She says she didn’t feel nervous. "I had spent years watching how the cut was done. And my daughter was a baby at the time, too small to understand what was happening. That’s the best age to do it."

In a matter-of-fact-way, Khidir talks about how she handles the aftermath of her work. She describes applying oak wood charcoal to reduce pain in the wound and sitting the child in a bowl of cold water and antiseptic solution after the operation. When asked about the specifics of the procedure she performs, however, she covers her face with her loosely worn headscarf and refrains from speaking too specifically.

"I cut about a quarter off with a razor," she says, in an apparent reference to the so-called Sunna circumcision, a mutilation that some clerics have attributed to a tradition taught by the Prophet Mohamed that involves removing the prepuce. Sometimes the clitoris is left intact, but sometimes part of or all of it is removed.

Dreaming of an End

Qalthum Murat, an advocate of secularism and modernity in one of the most socially conservative, tribal parts of northern Iraq, knows Khidir’s story -- and others like them -- all too well. She dreams of the day when she will hear them no more.

The 24-year-old spends four days a week visiting the women of outlying villages to bring basic health advice, largely to do with food and sanitation. Each of these days, she struggles with the divisions between rural and urban Iraqi Kurdish society.

Superficially, little separates her from women such as Khidir. She still lives barely 15 miles from Khidir’s village, in the scruffy, impoverished smuggling town where she was brought up, Raniya. She left school at 16.

Politics, however, have shielded her from genital mutilation. Her family sympathizes with the radical wing of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, the more progressive of the two parties that have ruled Iraqi Kurdistan since it broke away from Baghdad in 1991.

Murat has been a member of the local branch of the PUK’s Women’s Union since she was 15. Last year, Rewan, a women’s group based in the regional capital of Sulaimaniyah, invited her to join. The group has been fighting for a decade to eradicate female genital mutilation from Iraqi Kurdistan.

Mobile Health-Awareness Classes

Given a grant six months ago by coalition authorities to provide mobile health awareness classes to the women of the Pizhdar district, Rewan charged Murat with collecting data about the prevalence of female genital mutilation. The cassettes she plays to villagers--followed by a question-and-answer session--warn about the health dangers both of FGM and the widespread local tradition of marrying girls off very young.

Murat admits that the two sides of her work sometimes come into conflict. "The survey will only be accurate if I win the trust of villagers," she says. At the same time, she describes herself as being like an anti-FGM missionary.

More prominently associated with several countries in Africa -- where some traditional midwives are giving up their FGM work in response to public-health and legal efforts -- female genital mutilation is also practiced in the Arabian peninsula and other areas of the Middle East.

There are now some penalties for practicing FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan. Certified midwives caught operating on girls lose their certification. But activists admit threats of legal action rarely have any effect on traditional practitioners in the villages, who work in the secrecy of their homes.

The main problem -- as with other countries in the region -- is that statistics are totally lacking. A countrywide health survey done by the New York-based United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, between 1998 and 2002 returned no FGM data. Large surveys since the war have not touched on the phenomenon.

Better Data on FGM in Region

In areas of Iraq under Saddam Hussein’s control until last year, efforts to fill in the blanks left by that study have barely begun. In Kurdish areas, by contrast, attempts to quantify the phenomenon are way ahead. They began over a decade ago, as part of a wave of national regeneration that swept the region following its de facto secession in 1991.

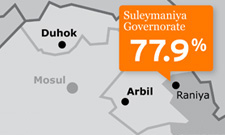

One of the first on the scene was Qalthum Murat’s colleague, Runak Faraj, editor of the women’s bimonthly newspaper published by Rewan since 1992. She has come to two conclusions; that the practice is limited to the southern half of Iraqi Kurdistan and is most prevalent in rural areas.

"In Sulaimaniyah city, figures suggest only 2-3 percent of women have been circumcised... almost all of them (living) in the poorer suburbs," Faraj says. In the remote border regions of Qaladze, Raniya and Pizhdar, meanwhile, she thinks female genital mutilation is almost universal.

There is evidence to back up her estimates

In Zurkan, Amina Khidir’s village, there are 300 families and three women who practice genital mutilation. In Raniya, professional midwife Khadija Zaher has been helping local women through childbirth for 14 years.

"It’s only in the last two years that I’ve begun to see women who have not been circumcised," she says.

Not everyone agrees that the practice is so common, though. "With aid money available to those with the most apocalyptic statistics, it is easy to exaggerate," warns Thomas von der Osten-Sacken, whose German nongovernmental organization, based in Sulaimaniyah, specializes in women’s issues. "I personally suspect that circumcision levels for women in the Sulaimaniyah governorate are much closer to 10 percent than the 40 percent suggested by some."

Beyond Statistics

But it is not just the absence of reliable statistics that hampers the work of groups like Rewan. There is also the gulf that separates practitioners from those trying to dissuade them.

"I often feel like the two Kurdish communists who went round villages trying to convince people that God was an illusion," laughs Qalthum Murat, referring to the anti-FGM cassettes she works with. "The villagers listened politely, brought tea, nodded gravely. At the end, one of them sighed, ’Yes, this is a complicated business, but God is great. He will find a solution."

For four years after she began her campaign to eradicate female genital mutilation in 1992, Rewan’s Runak Faraj found that her activists -- mainly secular-minded urban women -- were struggling to communicate with villagers. It was then that she decided to talk directly to the clerics who exert such influence over the local way of life.

"Of course, it was ultimately a decision of individual imams," she says, referring to the religious leaders. "Some refused to cooperate but most did. Two senior clerics in particular, Mullah Mohamed Amin and Mullah Mohamed Saleh, are now among the most active in the campaign to eradicate the practice."

Qalthum Murat is more pessimistic. "In almost every village I visit, it is the old women and the clerics who most strongly oppose my work. They accuse me of being an atheist and a member of the PKK," she says, referring to the extreme left-wing Turkish Kurdish armed separatist group that has its base in the mountains just behind Zurkan. "Unless local authorities begin to take the matter seriously, I am afraid it will be a long time before this practice disappears from the region."

Nicholas Birch is a freelancer based in Turkey and working throughout the region. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, The Guardian, The Christian Science Monitor, and The Globe and Mail.

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation