Middle East: FGM still largely an unknown quantity in Arab world

In a recent statement released to coincide with the day of Zero International Tolerance of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)on 6 February, the UN Children's Agency UNICEF noted that the Arab world had yet to make decisive moves in the eradication of the practise.

In a reference to Egypt, Sudan, Somalia and Djibouti, the press release went on to note that "so far, FGM prevalence rates of over 90 percent of women and girls have remained virtually unchanged for the past decade."

In the case of Egypt and Djibouti, those bald statistics mask a growing resolve on the part of local government and civil society to combat the phenomenon.

Following the example of the National Council for Childhood and Motherhood, over a dozen Egyptian NGOs are doing what one senior Cairo-based UN official called "a wonderful job" raising awareness of FGM through seminars and the media. Both Cairo and Alexandria universities are collaborating in the development of national campaigns.

Early in February 2005, at a conference organised by the government and international NGO, No Peace Without Justice, Djibouti announced the ratification of the Maputo Protocol, which bans FGM. After sometimes fierce discussions, participants finally agreed that no justification for the practise could be found in the teachings of Islam.

Yemen, where FGM levels in some regions are known to reach 50 percent, is another example where progress is being made. A January 2001 ministerial decree banning FGM, combined with government and NGO concentration on the worst-affected areas, have, in the words of Jordan-based UNICEF communication officer Wolfgang Friedl, "considerably reduced the frequency of the practise in the space of only a few years."

Further north in the Middle East, the record is considerably more patchy. Hampered by its policy of following up on an issue only if the local authorities themselves consider it important enough to investigate, the UN's statistics on FGM peter out on the Egyptian-Israeli border.

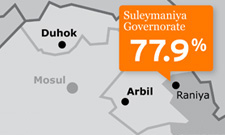

Yet FGM is known to be practised throughout the Arabian peninsular, particularly in northern Saudi Arabia, as well as in southern Jordan and Iraq. A recent survey by the German NGO WADI, based in the Iraqi Kurdish city of Sulaymaniyah, showed well over 60 percent of women in the rural area of Germian, about 150 km southwest of city, had been circumcised.

There is also circumstantial evidence to suggest that FGM is present in Syria. Then, of course, there is Iran. Given the frequency of the phenomenon in the tribal areas of Iraqi Kurdistan immediately adjoining the Iranian border, and the population's close familial and cultural links to the Kurds further east, it is only logical to assume FGM exists there too.

The problem, as one senior UN official well acquainted with the Middle East told IRIN, is the attitude of the region's governments. The coverage - or rather non-coverage - of FGM, he argued, can be compared to campaigns to stamp out honour killings.

"We know both Jordan and Syria have a problem with honour killing," he said. "But while Jordan is implementing new legislation forcefully, Syria simply does not want the issue to get out."

It's a point put more bluntly by Thomas von der Osten-Sacken, director of WADI.

"There is a clear link between freedom of expression and knowledge of FGM," he told IRIN in Istanbul. "If we know the phenomenon exists in Egypt, Jordan and Iraq, it is because these countries have an embryonic civil society."

The same, added the senior UN official, cannot be said for Saudi Arabia.

"Issues of FGM and violence against women in general are not open to discussion within the country, let alone to UN agencies," he said. "I can only hope the recent changes in the political environment there will enable us to find an entry point."

The one shining exception to the general lethargy impeding efforts to combat FGM is Iraqi Kurdistan, where women's organisations like the Sulaymaniyah-based Rewan have been fighting to reduce the practise since the region broke away from Baghdad in 1991.

Following its small-scale study in Germian, WADI is now on the verge of starting a survey of the whole of the Iraqi Kurdish region. Training of local students who will be doing the bulk of the field work is due to begin on 1 April. Research will be done during the summer holidays in order for the results to be published in November in Kurdish, Arabic and English.

"We're aiming to interview 1 percent of the total population of Iraqi Kurdistan," Osten-Sacken told IRIN. "That should provide the basis for a proper campaign to stamp the practise out.

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation