An End to Female Genital Cutting?

by Nicholas Birch

These are busy times for Pakhshan Zangana. Head of the women's caucus in the Iraqi Kurdish parliament in Arbil, she is on the verge of pushing through a piece of legislation that is the first of its kind in the Middle East — a law criminalizing female genital mutilation (FGM). "Sixty-eight out of 120 deputies signed our bill, so we could have got it passed by ministerial decree," Zangana says. "But law-making is the job of parliament, and we want everybody to debate this issue openly." The bill received its first reading on Dec. 3 and is likely to be passed by February.

Affecting up to 90% of women in Egypt, Sudan and Somalia, FGM is widely seen as an African phenomenon. But it also happens to a lesser extent throughout the Middle East, particularly in Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Iraq.

If the Iraqi Kurds are leading the way today, it is partially thanks to a handful of local women's organizations that have struggled for greater awareness of the issue since the early 1990s. But the real breakthrough came in 2005 when WADI, a German non-governmental organization, published the results of its survey of 39 villages in the Germian region, east of Kirkuk.

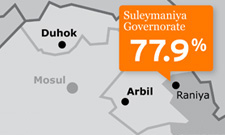

Of 1,554 women and girls aged older than 10 interviewed by WADI's local medical team, over 60% said they had undergone the operation. Larger surveys completed since show the practice is prevalent among local Arabs and Turkmen, as well as Kurds. The surveys provide the first solid statistics on a tradition which — while practiced relatively openly in parts of Africa — is so veiled in secrecy here that brothers are often unaware their own sisters are affected.

A farmer's wife in Zurkan, a remote village close to the Iranian border in northeastern Iraqi Kurdistan, Amina Khidir began performing the operation when her mother became too old to carry on. Her first patient was her own daughter. "I didn't feel nervous, because I had spent years watching how the cut was done," Khidir remembers. "And my daughter was a baby at the time, too small to understand what was happening. That's the best age to do it." Matter-of-factly, Khidir describes dealing with the aftermath of her work. She applies oak charcoal to reduce pain, cold water and antiseptic solution to reduce the risk of infection. Asked about the specifics of the procedure, she covers her face with her loosely worn headscarf. "I cut about a quarter off," she says. It's a reference to the so-called 'Sunna' circumcision, the removal of prepuce and sometimes clitoris that some Muslims attribute to a tradition taught by the Prophet Mohammed.

"According to the Shafi'i school [of Islamic law] to which we Kurds belong, circumcision is obligatory for both men and women," explains Mohamed Ahmed Gaznei, chief cleric in the city of Sulaimaniyah, Iraqi Kurdistan's second city. "The Hanbali [school] says it is obligatory only for men." Personally opposed to female circumcision, Gaznei in 2002 issued a fatwa, or religious edict, calling for imitation of Hanbali practice. He has since appeared on a short film about FGM shot by a Kurdish filmmaker that WADI medical teams now take with them when visiting villages.

"Look, they even got Osama bin Laden to talk," quips Gula Hama Amin, one of 30 women watching the film in Nura, a village 100 miles north of Sulaimaniyah, referring to Gaznei's luxuriant beard. The others tell her to quiet down. All have been circumcised for reasons hovering somewhere between religious belief and tradition: locals say the food an uncircumcised woman cooks is unclean, or that the operation makes a girl more affectionate to her family.

So great was the taboo surrounding FGM until recently that even the Iraqi Kurdish authorities, largely supportive of campaigns against it, have sometimes been tentative in their resolve to take action. Since 14,000 people signed an April 2007 petition for a law against FGM, though, the mood has changed radically. Both the region's main parties have given their blessing to the law, and FGM is now openly discussed by the local media. Back in parliament, Pakhshan Zangana knows the law represents only the end of the beginning of this struggle. Her aim now, she says, is to end FGM in Iraqi Kurdistan within five years. "A law on its own can't do that," Zangana says. "What can is full cooperation between government departments, and people like me, in parliament, making sure the law is enforced."

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation

Clinton: 'Cultural Tradition' is No Excuse for Female Genital Mutilation